Part VIII: Into the Second Century

When Tom Heller joined Moorhead Public Service in 1976, power economics in the Upper Midwest were in a state of change. The Rock Lake, North Dakota, native was fresh out of North Dakota State University with a degree in electrical engineering, and he found the challenge he wanted at the busy Moorhead Public Service Commission.

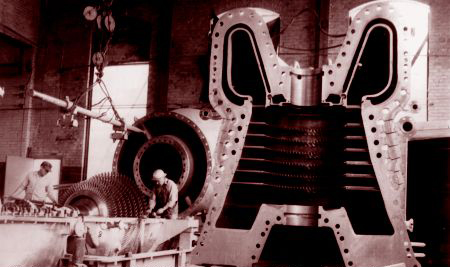

For one thing, Moorhead’s power plant was running at full capacity. The Commission had installed a 22,000-kilowatt Brown-Boveri turbine at the plant in the late 1960s, but because of the availability of cheap hydroelectric power from WAPA, the lignite-fired boiler and Swiss-made turbine were used primarily as a backup during most of the early and mid-1970s.

Still, the city was glad it had the power. In June 1975, the 69,000-volt tie to the WAPA hydro system in West Fargo was put out of commission by a vicious summer storm. "The poles were actually down," Heller said. "We spent a lot of time after that working on getting another feeder."

Eventually, the municipal utility installed a second substation on the WAPA line south of Moorhead in 1979, strengthening the city’s ties to the important source of federal hydroelectric power. But by that time, the WAPA pie had been sliced as thin as it was going to get. In 1977, WAPA had frozen allocations for Missouri River power. In essence, that meant that Moorhead and other preference customers in the Upper Midwest would get no more power from WAPA than they had received in 1976.

The 1977 freezing of allocations was no surprise to Moorhead or the other preference customers. As far back as the late 1960s, public power planners in the Upper Midwest had been aware of the limited resources afforded by Missouri River hydropower. In 1975, the Missouri Basin Municipal Power Agency, a generation and transmission joint action agency headquartered in Sioux Falls, South Dakota, and five other partners announced plans to build the Laramie River Station—a three-unit, 1,650-megawatt coal-fired power plant near Wheatland, Wyoming.

Also known as the Missouri Basin Power Project, Laramie River was scheduled to go into commercial operation by 1979. Moorhead was a member of Missouri Basin through its membership in the Western Minnesota Municipal Power Agency. In 1977, the utility signed a five-year contract with Missouri Basin to firm up WAPA hydropower for Missouri Basin members while Laramie River was being built.

The result was a windfall for the Moorhead Public Service Commission. From 1977-1981, the 22,000-kilowatt turbine at the utility’s power plant ran literally flat out, supplying power to Missouri Basin members.

"We ran the plant rather extensively over that five-year period," Tom McCauley said. The plant was burning approximately 700 tons of lignite coal a day, and morale among the workforce was higher than it had been in years. "When I left the Department in 1985, we had a year’s budget—about $10 million—in the bank."

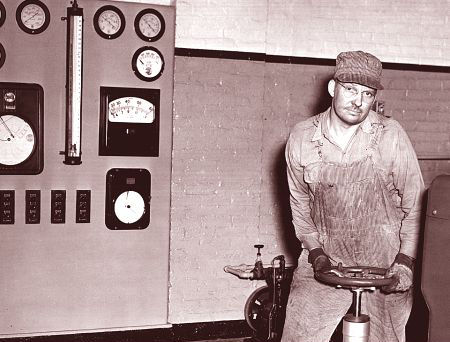

Moorhead's power plant ran flat out in the late 1970s, but by the time this photo as taken in 1988,

power plant operators like Ray Steele brought the plant up only for sporadic test runs

Tom Heller, who took over from McCauley as general manager in 1985, echoed his predecessor’s observations about the lease deal with Missouri Basin Municipal Power Agency. "We paid for that unit more than once," is the way he described the Brown-Boveri turbine. "In looking at that in retrospect, the plant has made money. It was a real success story."

The three units at Laramie River came on-line between 1979 and 1983, and the lease with Missouri Basin expired in 1982. Since then, Moorhead’s power plant has been run sparingly. The plant’s 10-megawatt gas turbine was leased to Missouri Basin in 1993 for reserve capacity, generating $90,700 in annual revenues to Moorhead Public Service over the next 14 years.

The Malt Plant Fight, and Another Strike

The late 1970s and early 1980s were difficult years for America’s electric utilities. The fragility of America’s energy supply line was revealed by Arab and Iranian oil embargoes in 1973 and 1979, and the cost of money shot up during the period, fueled by inflation and skyrocketing interest rates. The higher cost of building power plants like Laramie River meant sharply higher electric rates for customers. Utility workers, whipsawed by inflation that ate away at paychecks, became far more militant.

In 1983, the Public Service Commission proposed a 20 percent electric rate increase across the board. Although the Commission had made money on the Missouri Basin lease, much of that money had been transferred from the utility fund to the city’s general fund. With Laramie River coming on-line at a higher cost than originally projected, the cost Moorhead had to pay for that power escalated. Most of the 20 percent rate hike went to pay for higher costs of power for the 20 percent of its electric supply that Moorhead got from Missouri Basin.

In the spring of 1984, the 26 Department workers represented by the International Brotherhood of Electrical Workers staged a 10-day strike for higher wages. Workers were unhappy that their wages were not keeping pace with inflation. After ten days of walking a picket line, workers affiliated with Moorhead’s IBEW local returned to work with a 5 percent wage increase for 1984 and a 4 percent increase for 1985.

For much of the late 1970s and early 1980s, the utility had also been embroiled with city leaders in a dispute over economic development. Anheuser-Busch, the big St. Louis-based brewery, approached the city about locating a malt plant in Moorhead. McCauley, who was then the utility superintendent, feared that the plant’s water and power use would tax the utility’s system.

McCauley and Mayor Dwain Hoberg got into a protracted battle over the proposed Anheuser-Busch malt plant. Economic development proponents called for McCauley’s resignation, and the plant eventually was sited at Moorhead. McCauley, who did take early retirement in 1985 to become the manager of the municipal utility in Burbank, California, noted that the malt plant did become a good customer of the Moorhead utility. As it was, Laramie River proved to be one of the most efficient coal-fired generating stations in America. By 1985, Missouri Basin’s wholesale rates to Moorhead and other members began to drop significantly; Moorhead was able to pass along the rate cuts to its customers.

Heller, who served as general manager from 1985 until he left to become general manager of Missouri Basin in 1992, said one of his major goals at Moorhead was to institute processes to get more consumer input on decision-making, especially in the matter of water and electric rates. Rebuilding customer trust was important after a group of electric heat customers sued the utility over changes to the electric rate structure in 1980. The case never went to trial and was dismissed in the utility’s favor in 1983.

"By 1986, we were looking in-depth at certain issues from a customer perspective," Heller said, "particularly with conservation, the need for a new water plant, rate structures and the like. That was very successful."

Though the utility wasn’t formally created until 1896, the Moorhead Public Service Commission ended its first century of operations in mid-September 1995, with the dedication of a new water treatment plant built to meet the requirements of the Federal Safe Drinking Water Act. The utility served the 32,000 residents of Moorhead with water and electric power, returning nearly $3 million a year to the city’s general fund.

Residential electric and water rates remained low, as they had for a century. Residents in Moorhead paid 4 cents a kilowatt-hour for their electricity, less than half of what the average customer of an investor-owned utility paid. Residential and industrial water rates were comparable to those in nearby Fargo.

Residential electric and water rates remained low, as they had for a century. Residents in Moorhead paid 4 cents a kilowatt-hour for their electricity, less than half of what the average customer of an investor-owned utility paid. Residential and industrial water rates were comparable to those in nearby Fargo.

For the people of Moorhead, public power has been a vehicle to provide clean water and reliable electricity at the lowest possible price. For 100 years, Moorhead Public Service grew with its home town and proved conclusively that the citizens of the Red River Valley community knew what they were doing when they made Moorhead a public power community a century ago.

Planners had hoped that the expansion into the Buffalo Aquifer wells in 1950 would provide the city with clean water for as much as 30 years into the future. But the planners had estimated that the city’s population would stay relatively stable during the 1950s and 1960s. From 1950 to 1960, however, the city’s population grew by more than 50 percent, and the demand on the wells east of town proved far greater than anyone had estimated 10 years before.

Planners had hoped that the expansion into the Buffalo Aquifer wells in 1950 would provide the city with clean water for as much as 30 years into the future. But the planners had estimated that the city’s population would stay relatively stable during the 1950s and 1960s. From 1950 to 1960, however, the city’s population grew by more than 50 percent, and the demand on the wells east of town proved far greater than anyone had estimated 10 years before.

The third major change for the utilities department came in 1973 when a new city hall was erected as part of Moorhead’s Center Avenue Urban Renewal Plan. For much of the twentieth century, Center Avenue had been Moorhead’s commercial hub. But by the early 1970s, the Avenue was dotted with closed-up shops. However, City Hall, the Moorhead Police Department and the Moorhead Fire Department were all located along Center Avenue, and when the city announced plans to build a new City Hall on Center Avenue, it was envisioned as the cornerstone of an ambitious urban renewal project.

The third major change for the utilities department came in 1973 when a new city hall was erected as part of Moorhead’s Center Avenue Urban Renewal Plan. For much of the twentieth century, Center Avenue had been Moorhead’s commercial hub. But by the early 1970s, the Avenue was dotted with closed-up shops. However, City Hall, the Moorhead Police Department and the Moorhead Fire Department were all located along Center Avenue, and when the city announced plans to build a new City Hall on Center Avenue, it was envisioned as the cornerstone of an ambitious urban renewal project.

Between 1945 and 1949, however, production of kilowatt hours increased in a nearly straight line. Peak loads grew from 2,400 kilowatts in 1944 to 4,925 kilowatts in 1948, an average growth rate of 20 percent a year over five years. Load growth was predicted to top 10,000 kilowatts by 1956.

Between 1945 and 1949, however, production of kilowatt hours increased in a nearly straight line. Peak loads grew from 2,400 kilowatts in 1944 to 4,925 kilowatts in 1948, an average growth rate of 20 percent a year over five years. Load growth was predicted to top 10,000 kilowatts by 1956.

That did not mean that the citizens of Moorhead had to follow the trend. "The rise of these giant corporations is one of the outstanding features of the last 10 years," the backers of a power plant expansion admitted in 1925. But all of those towns tying into the high line were essentially giving up their independence, the water and light department backers pointed out. "When a city permits a public service corporation to monopolize the business of furnishing water, light, power and heat to its people," the backers noted, "it relieves itself from the responsibility of raising the money to provide these facilities for itself."

That did not mean that the citizens of Moorhead had to follow the trend. "The rise of these giant corporations is one of the outstanding features of the last 10 years," the backers of a power plant expansion admitted in 1925. But all of those towns tying into the high line were essentially giving up their independence, the water and light department backers pointed out. "When a city permits a public service corporation to monopolize the business of furnishing water, light, power and heat to its people," the backers noted, "it relieves itself from the responsibility of raising the money to provide these facilities for itself." The death of A.J. Warner in January 1929 meant that for the first time in 20 years, water and light commissioners were faced with the task of selecting a superintendent for the water and light department. In the spring of 1929, the commission announced its choice: Harold A. Warner, the son of Ambrose Warner. The younger Warner had begun working for his father when still a boy, and he was schooled in all facets of the utility’s operations; Harold’s brother, Herbert Warner, also worked for the water and light department.

The death of A.J. Warner in January 1929 meant that for the first time in 20 years, water and light commissioners were faced with the task of selecting a superintendent for the water and light department. In the spring of 1929, the commission announced its choice: Harold A. Warner, the son of Ambrose Warner. The younger Warner had begun working for his father when still a boy, and he was schooled in all facets of the utility’s operations; Harold’s brother, Herbert Warner, also worked for the water and light department. On January 1, 1937, residential rates dropped significantly. The old rates had been seven cents per kilowatt-hour for the first 35-kwh, five cents for the next 25-kwh and three cents for everything above 60-kwh. The new rates were 5.5 cents for the first 35-kwh, 4.5 cents for the next 25-kwh and two cents for anything in excess of the minimums.

On January 1, 1937, residential rates dropped significantly. The old rates had been seven cents per kilowatt-hour for the first 35-kwh, five cents for the next 25-kwh and three cents for everything above 60-kwh. The new rates were 5.5 cents for the first 35-kwh, 4.5 cents for the next 25-kwh and two cents for anything in excess of the minimums.